A Brief Look at Lahul, Zanskar and Ladakh

by Jack Ashcroft

If you glance at a map of the Himalaya, extending across to the north of India, it is approximately 900 miles between Godwin Austen K2 in the Karakoram and Everest in Nepal much the same distance as from north to south of The British Isles. The terrain of the landscape contrasts vividly in both cases, but the tract of country between K2 and Everest is the greatest contrasting landscape in the world it ranges from tropical forests to mammoth rivers and contains the world’s highest snow and ice clad mountains from which issue the world’s longest non polar glaciers. It also includes the high plateau desert landscape that characterises the country of Ladakh, close to the Karakoram. Ladakh is a very dry area, as indeed is the Karakoram itself. However, the mountain peaks of both Ladakh and neighbouring Zanskar rarely reach 7,000m whilst those of the Karakoram exceed 8,000m, giving that little extra precipitation.

If you wish to visit the Himalaya during July and August, the areas of Ladakh, Zanskar and the adjacent province of Lahul and Spiti are the places to plan for. The further east you go towards Nepal, the more rain you can expect in the monsoon period.

Enough of this meandering introduction suffice to say that with August our only choice of holiday, Harry Woods and I planned a trek in 1982 through the Zanskar Valley from Lahul to Kishtwar. We covered 180 miles in just under three weeks over the Shingo La 5,096m to Padam 3,600m , the capital of the Zanskar Valley and then out again over the Umasi La 5,300m an eight day trek of contrasting terrain, from the desert like landscape of Zanskar through lush green forested gorges down to Kishtwar.

General Bruce, having reached a 20,000ft summit to the east of the Shingo La in 1912 wrote: “Zanskar to the west, though bare enough compared to his view east in all conscience, is wild, broken and savage to a degree a more inhospitable country it would be hard to find but some of the peaks are fine and boldly shaped… the great difficulty in Zanskar… is the number of streams to be negotiated… its intense savageness attracted me.” He goes on to say that the people who live there must be very hardy and able to withstand great cold.

It is this country one enters on the ten day trek from Darcha, the police post in Lahul, to Padam. Our trek also included a diversion to visit Phuktal, the most impressive monastic site in Zanskar. Bruce pointed out that the country is “wild and broken” but that the people are reasonably kind and interesting, inhabiting the highest settlements of any size in the world.

Kargiakh and Thangso at 4,200m over the Shingo La have no doubt been the frontier posts between Zanskar and Darcha for thousands of years and only recently has the policing stance been eased. This is indeed a dry and bleak environment, certainly the most spartan I have encountered in my three visits to the region but welcome after the three day trek through the virtually uninhabited country from Darcha and its many “streams to be negotiated”.

Michel Peissel, an anthropologist much travelled in the Himalaya, gives good insight into the Ladakhi character. His book “Zanskar the Hidden Kingdom” is a very readable description of a walk through Zanskar, only two or three years after Ladakh was opened to tourism, the borders having been closed by the Indian authorities from the end of the Second World War.

There is much to write about in nearly three weeks travel through these ancient sparsely populated valleys, but suffice to say that it was a pleasant relief and a revelation to walk into Padam having followed wild and broken gorge after gorge for over a week. Padam, with its population of a thousand or so, is the capital of Zanskar effectively half way along a hanging valley some eighty miles long with oasis like settlements surrounded by mainly dry, barren, mountains. The only ways out lie over passes of some 4,000m to 5,000m to the north, south and west. To the east is the outlet of the Zanskar River, not a feasible route in summer, we were told, but in winter becoming a hundred mile frozen highway giving access from Padam to Leh the Capital of Ladakh and the confluence with the embryonic Indus far to the north. Peissel’s description of Zanskar “The Hidden Kingdom” is indeed an apt one.

We stayed in Padam for two days and then set out on our eight day trek over the Umasi La to Kishtwar and Kashmir. The Umasi La is a more serious pass than the Shingo La and is surrounded by interesting peaks. It had been our intention to camp for two nights high on the pass with a peak in mind but this was not to be. We climbed to the pass near the summits but only stayed for twenty minutes as the weather was blowing in from the valleys of Kashmir. We resolved to get down the glacier on the far side as soon as possible rather than camp high, an hour’s descent through jumbled ice falls and moraine snow in poor visibility.

What were the highlights of our trek? Perhaps “highlights” is the wrong description, but the contrasting temperatures in Zanskar certainly come to mind from one hundred degrees fahrenheit at high noon to below freezing at nights the Buddhist culture in Zanskar and the contrasting Moslem culture down in the valleys of Kishtwar the unclimbed peaks of considerable interest around the Shingo La and Umasi La, not too huge and clustered more dramatically above the Umasi La not to mention crossing the streams and keeping the party together! On our approach to the Umasi La we managed to end up with Harry and I on one side of a glacier snout and melt waters quite extensive at seven o’clock in the evening and with our porters, tentage, food and sleeping bags on the other side. Our lot was a forced bivouac at 16,000 ft at the side of a crumbling glacier snout with thoughts of snow leopards, until the dawn arrived and we eventually found our way through the jumbled terrain to our two porters and a welcome meal.

It was a fine trek. We were a little austere in our planning with a very basic diet and at the end of three weeks it certainly felt as though some energy had been expended! The weather was kind with only one and a half days of poor weather in eighteen unluckily the one poor day was the day we traversed the Umasi La. In 1984 Harry and I were joined by other Sheffield based climbers for another visit to Ladakh. This time eight of us travelled out to India at different times in July and August to meet up in Leh some sixty miles north of the Zanskar valley. The fact that we managed it at all was remarkable, as Kashmir and Punjab were not in a very settled state at the time and we had made contingency plans to go further east to the Garwhal if Leh proved inaccessible. Despite having travelled out in four separate groups, all eight of us including Frank and Jennifer Mellor met up in Leh during the first week of August for a trek in the Marka Valley.

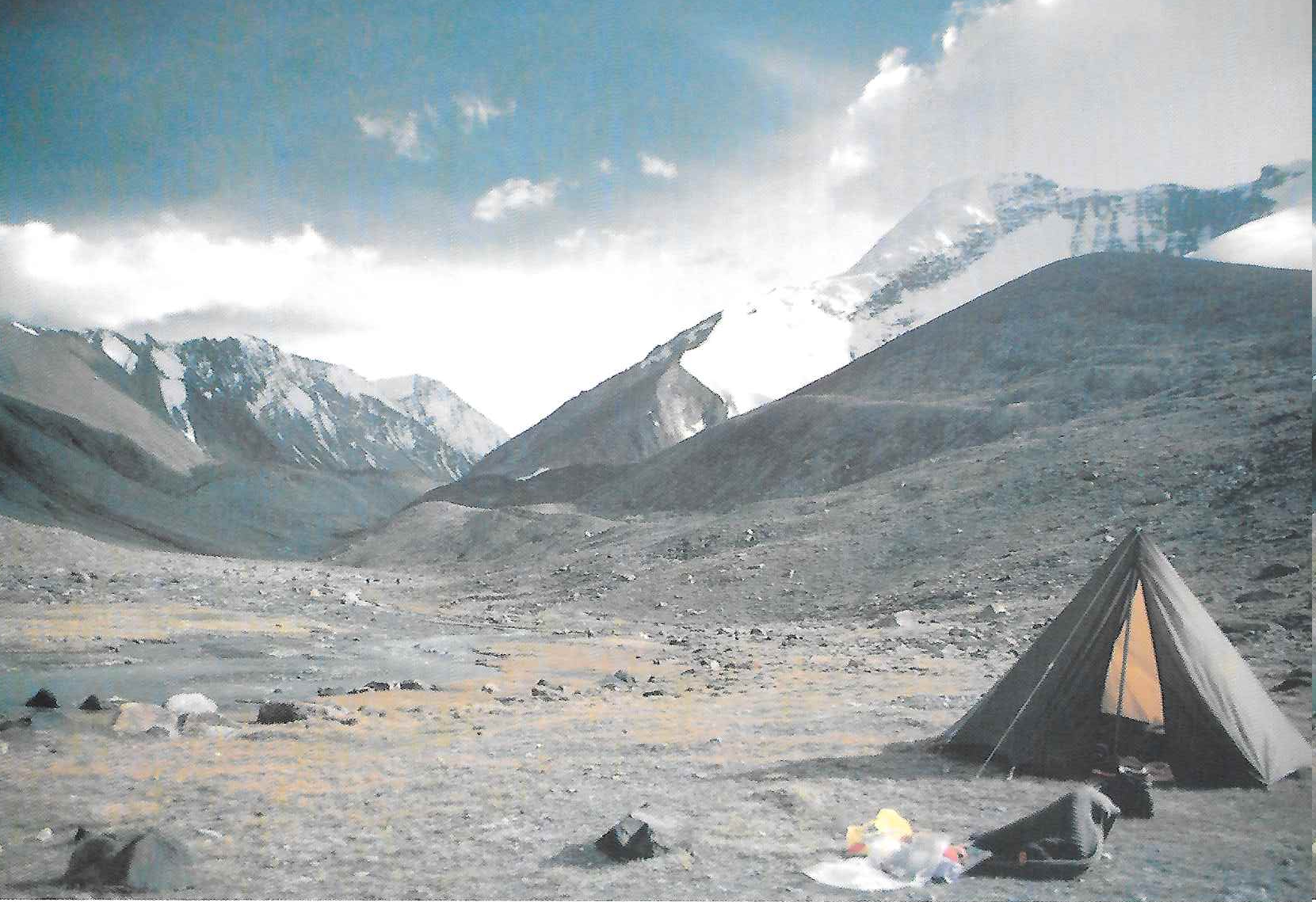

I can thoroughly recommend the Marka Valley as an experience in gentle Himalayan travel, certainly the way we did it and particularly in contrast to our trip of 1982. Taking advantage of the tourist office facilities in Leh, we took with us an Indian Mountaineering Foundation Guide and two horsemen. The Marka Valley trek is a regular summer tourist route of some seventy to eighty miles, a round trip from Leh which crosses two passes, the Ganda La 4,450m and the Longmaru La 5,220m . From the Ganda La we had a rather hazy view north west to the Gasherbrum K2 massif and south to the Kishtwar peaks. We had planned a trekking peak ascent which turned out to be a sortie into the Kang Yissay group. We established base camp at about 5,000m in an idyllic situation and attained the north summit of Kang Yissay 6,090m and a subsidiary point La Ribla 5,960m on the opposite side of the Kang Yissay glacier from the principal peak.

We were eighteen days on this trip including four at base camp. The highlights of the holiday were many. Leh, being the capital of Ladakh, has a military garrison and is on the centuries old Karakoram Pass trade route between Tibet and India it is more in touch with twentieth century living than Zanskar. Nevertheless, three of us are fairly convinced that we saw and I’ve got to use the expression a “Yeti like creature” leap over the boulder strewn slopes of Kang Yissay at five o’clock in the morning soon after we had left base camp on our eleven hour day on the peak. Our first impression was reinforced later when we failed to recognise the species on referring to the flora and fauna of the region on our return to Leh.

The Hemis Gompa, some three hours by bus from Leh, is a fine example of Buddhist architecture some five hundred years old. Even better is to walk 1,000 feet above Hemis to the tiny sanctuary of Goatsang where the Lama regularly scrambles up Grade IV rock routes to maintain the prayer flags that span the valley. Hemis is the centre of the Buddhist festival held each year in May after the winter snows which cut off the valley from October to April have receded to allow thousands of pilgrims to visit Ladakh.

This article hardly does justice to our visits to Ladakh in 1982 and 1984. I quote from the pre war writing of Dr. Tom Longstaff: “Walk for a week or ten days from Simla along the Hindustan Tibet ‘road’ make a camp in the first valley south of the Satlaj that takes your fancy: from here climb all the peaks on both sides of the valley and you will have had as much good climbing as in an Alpine season and for the same expenditure, if your party consists of not more than three good climbers who can muster enough Hindustani to do their own job for themselves. Here is both pleasure and high mountains. The scale is bearable: on the giants is only labour and weariness: they are best to look at.” I would not argue with this, but I am sure that I do not need to remind anyone of the necessity for fitness before getting to altitude, followed by a sensible period of acclimatization. After that, the usual medical precautions to fight the stomach microbes on a short holiday in India are essential for both “pleasure and high mountains”. As a postscript, do study your logistics. We were a little short, to say the least, on our porterage when crossing the Umasi La in 1982. If our two porters had not been prepared to carry such heavy loads we would not have made it over the pass, and as a result of their heavy loads, they fell behind on the ascent and we ended up on opposite sides of the glacier snout that August night in 1982.

The mountains of Ladakh are many and varied, most of them awaiting first ascents. Once one moves north over the passes of Kulu, Chamba and Kashmir one enters a new world “Little Tibet” as it has often been called. It is a pocket of high plateau where India meets China in both the geographical and political terms of today. The area has never been released from the tensions which existed in the post war period and it now needs care in its future development, particularly in relation to tourism. The signs of rapid progress are already there and I hope that the mountaineering fraternity will observe the rules. Have you purchased your “Ladakh Zanskar” guide book yet?

Figure 1: Base Camp Below Kang Yissay Ladakh